|

|

|

|

|

Historical Landmark No. 718 Point Loma Community Historical Landmark No. 718 - Designated June 2005 |

|

|

| ||

|

|

Point Loma's Varied Architecture This 1933, two-story house at 3120 Owen Street is important for its architecture, which is a rare Southern Plantation Colonial Revival style in the La Playa community of Point Loma in the City of San Diego. It is located on Lots 3 and 4 of Block 158. The architecture of the house is important because it reflects the development of La Playa’s architectural shift from the popular Spanish Eclectic style to variations on Colonial Revival variants of early American history. Research at the San Diego Historical Society revealed only one other of this style on Point Loma and one in the City of Coronado. Although there may be a few others within the City of San Diego, no examples of Southern Plantation Colonial Revival style architecture have been landmarked by the City of San Diego. It is the only one of two known for all of Point Loma, and the first of this style nominated to the City of San Diego for historic landmark status. | |

|

|

Alice Evalyn Strawn was born in Boone County, Missouri on February 9, 1881 (California Death Index). Her mother was Alice Maupin Strawn who died in 1890. Her father Joseph was born in 1839 in Boone, Missouri and he and Alice Maupin married on January 14, 1868 in Missouri. They had five children and Alice Evalyn was probably the youngest of the five siblings. She married Joseph Loris Strawn and they came to San Diego in 1911 and lived at 3590 3rd Street until coming to Point Loma. Alice generally referred to herself as Mrs. J. Loris Strawn, which distinguished herself from her daughter of the same name. She was a San Diego resident for 54 years and died in a hospital on August 21, 1966. Little is also known of Joseph Loris Strawn. He was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in 1885, married Alice Evalyn Strawn, and by 1904 had their first of three children who would be born in Pennsylvania. In 1911 they moved to San Diego from Philadelphia for unknown reasons. (Pennsylvania 1910 Miracode Index online database) Although they are not listed in the 1911 directory, the 1912 directory lists them with no occupation and they were living at 4245 Stephens in Mission Hills (near the Francis W. Parker School). | |

|

|

The 1914-1918 directories show he worked as a salesman for J.W. Leavitt & Company selling automobiles and they lived at 3356 Albatross, west of the north corner of Balboa Park. An advertisement in the San Diego Union on January 4, 1920 shows he co-owned Bradshaw & Strawn, authorized service station for Oldsmobile and Chevrolet repair, which was located at 1132-1134 First Street in San Diego. Classified ads offered easy terms on 1917 and 18 Buick Roadsters and 1919 Chevrolet “4-90” Touring cars on easy terms, “we will take your Liberty bonds at par.” Another ad on January 1, 1920 shows he employed thirteen mechanics and another ad in the same paper showed they sold used autos. He later worked his way up as sales manager at Davies Motors for twenty years (San Diego Union July 18, 1934). J. Loris Strawn died at age 49 at his new home at 3120 Owen Street after two months of illness on July 17, 1934 (San Diego Union July 18, 1934). His obituary stated he had come to San Diego 22 years ago and was in the automobile sale business for 20 years. | |

|

|

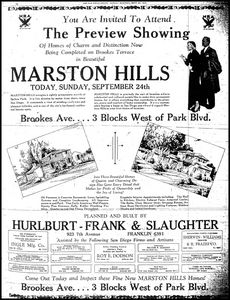

Alice Evalyn Strawn retained the services of Ralph L. Frank, as indicated on the surviving blueprint construction plans and Specifications kept in the house. Born in 1898 in Kansas, he served in the United States Navy during World War I and mustered out to become a salesman. The 1925 Directory listed him as salesman for Grable-Francisco-Bleifuss Company and he lived with his wife Alice at 3209 Homer in the exclusive Loma Portal neighborhood of Point Loma. That firm sold real estate and had branch offices in East San Diego, Encanto, La Mesa, and Los Angeles. H.D. Grable also distributed automotive supplies at their office at 1029 11th Street in downtown San Diego. Although Frank drew the plans from his office at Hurlburt, Frank and Slaughter, he also designed homes on his own and in this case the plans reflect his name only. Alice Evalyn Strawn did not hire Hurlburt, Frank and Slaughter to design, build, and furnish the home. The architectural plans clearly show Frank’s name and Hurlburt’s address. Frank went to work as a draftsman for Ralph E. Hurlburt in 1926 and he advanced to become a partner by 1933. The following year, he and Alice moved to 3106 Laurel. Although Hurlburt listed himself as a realtor with offices at 923 7th Street, his firm designed spectacular custom-built houses and mansions until he died in 1942. What distinguished the Hurlburt, Frank and Slaughter-designed and built houses was the marriage of architectural design with fine quality construction and high fashion interior design. According to Historian Kathleen Flanigan, “Ralph Frank, an architectural and interior designer, associated with Hurlburt in the early 1930s and created a number of houses independently starting in 1926. His residence at 2288 Juan Road in Mission Hills was also of his design.” (Flanigan, 2002) Among the houses credited to him with Hurlburt and Slaughter is the Frank H. and Margaret Burton / Milton P. Sessions House, Historic Landmark #534, approved by the Historic Resources Board on August 28, 2002 located in the prestigious Marston Hills Tract in Mission Hills. The Strawn House appears to be one of Frank’s independent creations in this period when he was also designing the exclusive Marston Hills community. | ||

|

|

The December 9, 1933 Notice of Completion, identified N. Anderson as the builder and he also signed Frank’s specifications copy which has survived to the present owner. Born Nelson Anderson on April 16, 1868 in Sweden, Nels Anderson was listed in the 1930 U.S. Census as 61 years of age, immigrated to the United States in 1877, married to 55-year old Nina, building contractor by trade, and owner of a $20,000 house. The 1933 Directory placed Nelson and Nina Anderson at 4039 Richmond and living with W.E. Anderson, U.S.N. Water Permits were obtained in 1926 by J.C. Allison but the General Conditions of Frank’s Specifications dictate that the General Contractor was to connect the house with the water meter in the street. | |

|

|

A feature article on Hurlburt, Frank and Slaughter’s Marston Hills project explained the partner’s roles in the company (San Diego Union January 28, 1934). Frank designed and planned, Slaughter constructed, and Hurlburt sold the houses. A later article described the houses as “Monterey design finished in early American style supplemented with modern conveniences” (San Diego Union March 4, 1934). The lighting fixtures were English brass to harmonize with “the early American paper and tone of the homes.” | |

|

|

Monterrey Transition to American Colonial Revival Design The Great Depression substantially impacted America and 1930 to 1932 were the hardest years for San Diego. When people began to pull out in 1933, they no longer wanted Spanish Colonial or European variant styles for new housing. Federal Housing Authority (FHA) programs to provide homes for needy families promoted New England Cape Cod and American Colonial Georgian and Federalist style houses as a sort of patriotic hope for pulling out of hard times. Magazines of the New Deal era after 1931 heartily promoted a variety of Colonial styles, as can be seen in this magazine cover from the September 1931 American Builder and Building Age (left). Houses promoted by Hurlburt, Frank and Slaughter in 1933 reflected the shift from Spanish to American styles. For example, a large advertisement with National Recovery Act (NRA) symbols at the top announced “Homes of Charm and Distinction Now Being Completed on Brookes Terrace in Beautiful Marston Hills” (San Diego Union September 24, 1933). The photos show a two-story Cape Cod house with shuttered windows and vertical board and batting upstairs siding and a two-story California Monterrey style house with upstairs balcony. The latter style transitioned out the former Spanish style housing, emphasizing California’s own contribution. A week later, the company published another ad showing “Monterrey Homes” with a mix of Cape Cod shuttered windows, full upstairs balustrade covered with a shake shingle roof, and side buildings in vertical board and batting siding. This design is striking similar to Frank’s design for 3120 Owen Street. | |

|

|

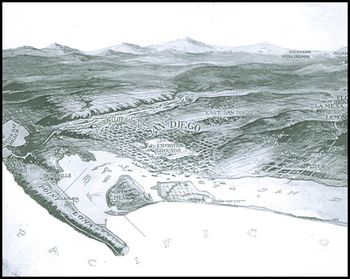

The early history of Lots 3 and 4 is also fascinating because during the post Civil War 1860s through 1880s many envisioned the terminus of a transcontinental railroad ending in La Playa. The rail’s proposed path went right through these two lots, explaining the presence of the San Diego & Gila Southern Pacific & Atlantic Railroad, the Memphis, El Paso & Pacific Railroad Company, and the Texas & Pacific Railway Company in the lot’s early chain of title. During the post Civil War 1860s through 1880s, the residents and power people in San Diego believed a railroad would connect the East Coast of America with the West Coast and they were confident the southern terminus in California would be at La Playa. Speculators predicted that the path of the track would run directly through Lots 3 & 4 of Block 158. Business leaders in the early 1850s contended La Playa should be the site of city hall and lobbied representatives in the U.S. Congress to extend the railroad to the small port. Among those Congressional railroad champions was Representative William S. Rosecrans. On December 21, 1868, the City Trustees sold rail development rights on Lots 3 and 4, Block 158 to the San Diego & Gila Southern Pacific & Atlantic Railroad. That company sold the rights to the Memphis, El Paso & Pacific Railroad Company on October 22, 1869. The rights must have expired, for the City Trustees sold the rights to C.M. Arnold on June 15, 1870 and then leased to The Texas & Pacific Railway Company in 1872. The following year on January 4, 1873, they sold to James A. Evans and the same day he sold rights to The Texas & Pacific Railway Company. Two months later, the San Diego & Gila Southern Pacific and Atlantic Railway Company granted their rights to The Texas & Pacific Railway Company. The title exchanges continued through 1884. In one day, the land changed hands in Quiet Title from The Texas & Pacific Railway Company to Hamilton, to Judge Oliver S. Witherby (an Escondido rancher), to Henry B. Williams. He sold to George B. Wilbur, who sold to the San Diego Land & Town Company on September 13, 1881 and they sold to S.H. Crippen and Frank S. Jennings on September 14, 1887. Almost overnight, the La Playa Rail Terminal scheme evaporated and the property again became available for residential development. The rail companies continued to quit claim and quiet title through the 1880s. A retrospective article in the Ocean Beach News in 1937 summed up Point Loma’s fate after the railroad prospects fell through: “With the failure of securing a railroad terminus the building of a beautiful residence section began and Point Loma is now approximately one half occupied with the prospect that in another ten years there will be very little vacant property and home sites here at a premium.” | ||

|

|

Permission to use this material is granted provided it is attributed as follows: Copyright © 2010 Ronald V. May and Dale Ballou May, Legacy 106, Inc., www.legacy106.com | |

|

|

Home | Designations | Qualifications | Company Profile | Newsletter | Links Archaeology

& Historic Preservation www.legacy106.com |

|